What You Need to Know Before You Outline Your Book

/Buddha said, “Nothing is forever except change.” In other words, the only thing that doesn’t change is that everything always changes. We might sometimes forget this in life, but it’s essential to remember in your writing. Whether you’re working on fiction or nonfiction, a the outline for a book is basically a chain of changes that climaxes into a major transformation. If you’re writing fiction this happens through a series of scenes that reach a climax. In nonfiction, especially self-help, this is done through a series of chapters that lead to a major result.

Usually, major changes in love, health, spirituality, or finances come through a series of smaller turns, even if we only recognize them in hindsight. In your story, this will be the outline that leads to the climax and eventually the resolution. It’s actually a very natural shape that occurs again and again in our lives, in ways big and small: a problem or desire intensifies like a wave until it breaks.

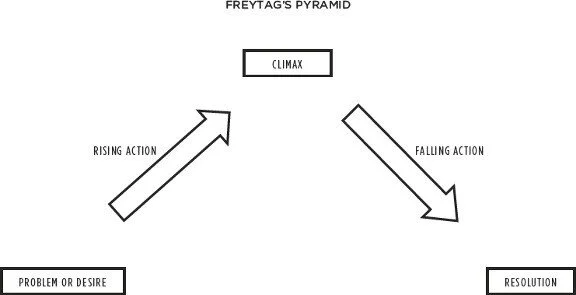

Thus, before we break out our outlining tools, let me introduce Freytag’s Pyramid. Gustav Freytag was a nineteenth-century intellectual who noticed this pattern in Greek tragedies, but today his pyramid can be seen everywhere, from novels to music to TV commercials. As we dive deeper into these principles, you´ll find thousands of examples of narrative arc.

In Freytag’s Pyramid a wave is initiated by a problem or desire that intensifies through the rising action until it reaches a climax and something is forced to change. After that the consequences of that big change fall into place, and the wave settles back into balance, where it cheerfully or tearfully resolves.

To initiate this wave, let’s take a deeper look at fear and desire. Fear and desire make up the emotional core of any book. If you’re writing fiction or narrative memoir, this is the driving force behind your main character. If you’re writing self-help, this is the reason that readers buy your book. It’s all wrapped up in what we want more than anything, and what we want to get away from more than anything. The more you make this clear right from the beginning, the more you’ll engage the attention of your reader.

Sinking into the driving emotions of the book makes the rest of the outline easier to write. Some people might say that outlining takes away the mystery and they prefer to let the book reveal itself as they go. I’d simply like to propose that clarity is your friend. First and foremost, I promise not to take away any mystery, mysticism, or adventure from the creative process. I couldn’t if I tried.

Although I always begin with an outline, the structure of my manuscript changes dramatically on a monthly (sometimes weekly) basis. Especially in the beginning.

However, I’m a huge fan of harnessing every drop of clarity that’s available at the begining. You can always delete stuff or move it around, but if you lose pieces of the initial vision as you dive into the thick of it, it’s hard to get them back. You don’t have to sketch out everything, just do as much as you can. Also, proposing structures to play with can draw out the idea in more detail. So let’s get into it. Here are two different structures, one for narrative memoir and fiction, and another for self-help.

With narrative, the three-act structure is a great place to start. Dive into the protagonist’s fear and desire, then imagine three major turning points born out of that driving force. Each turning point should (by definition) lead to a major interior and exterior change in the character’s life. This divides your initial idea into three major sections or events. Then fill in any scenes you can think of that will lead up to that turning point. The more you can integrate a tangible turning point into every scene, the more compelling your book will be. You want to create a very tight chain of change.

With nonfiction self-help, the same principal is at play. Each chapter should lead the reader to a specific outcome or change, and within the chapter you should provide stories or anecdotes that illustrate that change. To get started I often ask authors to pick a number between 1-10. Say 5. Then I ask them to tell me the five steps that would lead to the outcome of the self-help book. You might end up with more or less than five steps, but choosing a number gets the gears moving.

When you piece together these building blocks, you will find that the big wave of your narrative is made up of many little waves. Speaking of waves, working on outlining narrative arc always reminds me of a particular quote by Thich Nhat Hanh, “Enlightenment, for a wave in the ocean, is the moment the wave realizes it is water.” Any problem, story, or adventure in life is a fear or desire that initiates a rising wave of intensity until it breaks and unifies with the ocean again.

That’s why I admire anyone who embarks upon this process, because as you develop the capacity to understand strongest passions and pain as a wave, both in the beauty of their intensity and safety of the ever-present witness, you can see yourself as the ocean—as water. Making art is all about objectifying subjective experiences. The waves that may have once dominated our lives are free to crash back into the ocean.